»Forgetting the Dictator is a Form of Therapy«

BELARUSIAN MUSIC IN EXILE/WORLDWIDE

Probably the most famous DJ from Belarus–on the energy of exile, building senses through the universal language of music, and hungry youth culture worth of sounding worldwide

How did you get to Poland? What was your first experience of emigration? Why Poland–did you even have a choice?

When the »men in black« rang my doorbell for the second time, I thought that they were unlikely to come with an apology for the arrest or inhuman conditions of my imprisonment in Zhodzina prison. And I decided that my health seriosuly shuttered after Covid and only starting to recover, needed a completely different company.

Thus, an hour later I found myself at the airport. I had a Polish visa, issued for culture workers, and Poland itself had already been open for tourists for three days. Quequing at the Warsaw airport, like many other Belarusians, I thought it would not last long. Although, whatever hard I tried to calm myself down, the feeling of orphanhood was rising in my throat with the first breaths of the air at the station square–and it took me a long time to get rid of this sensation of bitter stinging.

I felt the most acute feeling of emigration after returning from the Department of Refugees. Sitting on the bed in a room of the hotel located in the building of the former convent–now, a culture center closed for the year of lockdown, I felt like I was in neutral waters.

»I’m no longer there, but neither am I here yet,« I thought. And the search for an answer to the »where then?« question became the starting point of my numerous new existential processes, which, fortunately, found a way out through creative projects.

Art campains, publications, exhibitions, book releases, performances–all these have become my own means of processing new experiences, not to mention the direct therapeutic effect. Art therapy is a unique means of self-analysis.

It was a period of universal belief in the inevitability of change. A keen interest in what was happening on the other side of the Bug river gave rise to the whole chain of incredible meetings with people who opened their hearts in a sincere desire to help. And this experience deeply touched me and, I should admit, made me a better person. Morevoer, the impossbility to return back to Belarus, as well as a forced obligation to speak on behalf of those forcibly deprived of this right helped me move forward.

At what stage of emigration did you come up with the idea of »The Anti-Hero with a Thousand Faces«? Why was it important for you to raise the topic of the antihero, dictatorships, and responsibility?

It happened at the stage when I accepted emigration and realized that I had crossed a certain line between »there« and »here« and became aware that, even accepting the collateral damage, it was not a drama, but rather a challenge that was worth a reaction from my side.

To be born again one must die, or at least die while alive. After all, only death can reset the accounts, giving us a unique chance to live another life. But then you must forget and, quoting my performance’s anti-hero »Forgetting does not mean betraying, in this case it rather means, through one’s own death, to give up the right to remember and to transfer it to the public domain. And it’s cool to step off from one’s life line on the palm stained with dactyloscopic ink.«

In the process of self-analysis, I realized that forgetting is a super task. Having gained the opportunity to look at myself »from a distance,« I discovered in my consciousness deep imprints of life in the totalitarian space and one could hardly forget them without the awareness and recognition of both one’s own role and responsibility.

One of such »imprints« is the image of the dictator, created and replicated to the point of obsession. Mass media brought this image to universality and, unfortunately, it is now deeply rooted in our collective consciousness.

»Forgetting« the dictator is a problem- and action-oriented form of therapy that involves changing behavior, emotions, and thinking patterns. The process is rather unpleasant and painful, but it still seemed relevant to me, so I decided to use a performative form to outline the path one should take to get rid of such »imprints.«

The project itself has a few parts and dimentions at which it works–theatrical, performative, and finally purely visual, photographic? How did you decide on the choice of language and art genres and how do those complement each other?

Leaving the state of the victim and accepting the challenge, you start moving towards gaining new experience. It is important to realize that what happens to you is not unique at all. All that you can do is either refuse and remain in liminality, or go on a journey, becoming the hero of a monomyth.

In fact, this is the universal motif of the adventure and transformation of the archetypal hero described by Joeseph Campbell, which I took as the basis of the plot structure of my performance »The Anti-hero with a Thousand Faces« where the protagonist goes through all the main stages of transformation, including the realization of one’s own responsibility.

There is a performative part in the play, which I will not disclose in order not to deprive the live audience of the opportunity to experience this emotion. I will only say that it serves as an instrument for measuring the viewer’s response to the transformation of the main character. This is part of my tribute to the artist and performer, political prisoner Ales Pushkin, who died while serving his term in Belarusian prison in 2023.

For storytelling, I use various forms, including photography. In 2020, I captured on film all the main threads of these complex and dramatic events. But in the performance, the images of these events no longer work as a document, but as a description of the call of time to which the main character responds, starting his journey.

Or, for example, scenography. It is fully multimedia. These are eight dynamic elements for eight walls, conceived by me as symbols of the stages of the traveler’s transformation, each of which, interacting with the hero, depicts him as a microcosm in the universal macrocosm. Something like the Vitruvian man, which sometimes fits into the symbol, sometimes violates its boundaries, and sometimes gets completely lost without it. This interaction with symbols allows me to describe plastically the signs of this small group at the moment of merging with a larger social body.

And by the way, speaking of signs, one of the parables in Kafka’s novel »Process«, which I use in the chapter »The Inner Guard«, in my opinion, very accurately describes other signs of this group, signs of the refusal of personal independence and the acquisition of authorized comfort in fear, in front of freedom and by choice, turning three decades into several pages of an eternal novel, making the story of my hero universal, which is what I really strived for.

And who are you in all these parts? What role do you play and what position do you take?

Exploring the universal images of »heroes« and »anti-heroes«, rooted in the collective consciousness, I thought not only about the domination of negative images over positive ones, but also about their original source, their replication and the author’s personal responsibility in this. Here the German philosopher Gadamer came to my aid. The image, according to him, is inseparable from what it depicts; it does not refer to it, but in a way represents it directly–allowing it to »appear.« It is precisely because of this existential continuity of the image that it performs the »increase in being« of the depicted. In a universal sense, art and photography, in particular, provide the »increased visibility« to human existence.

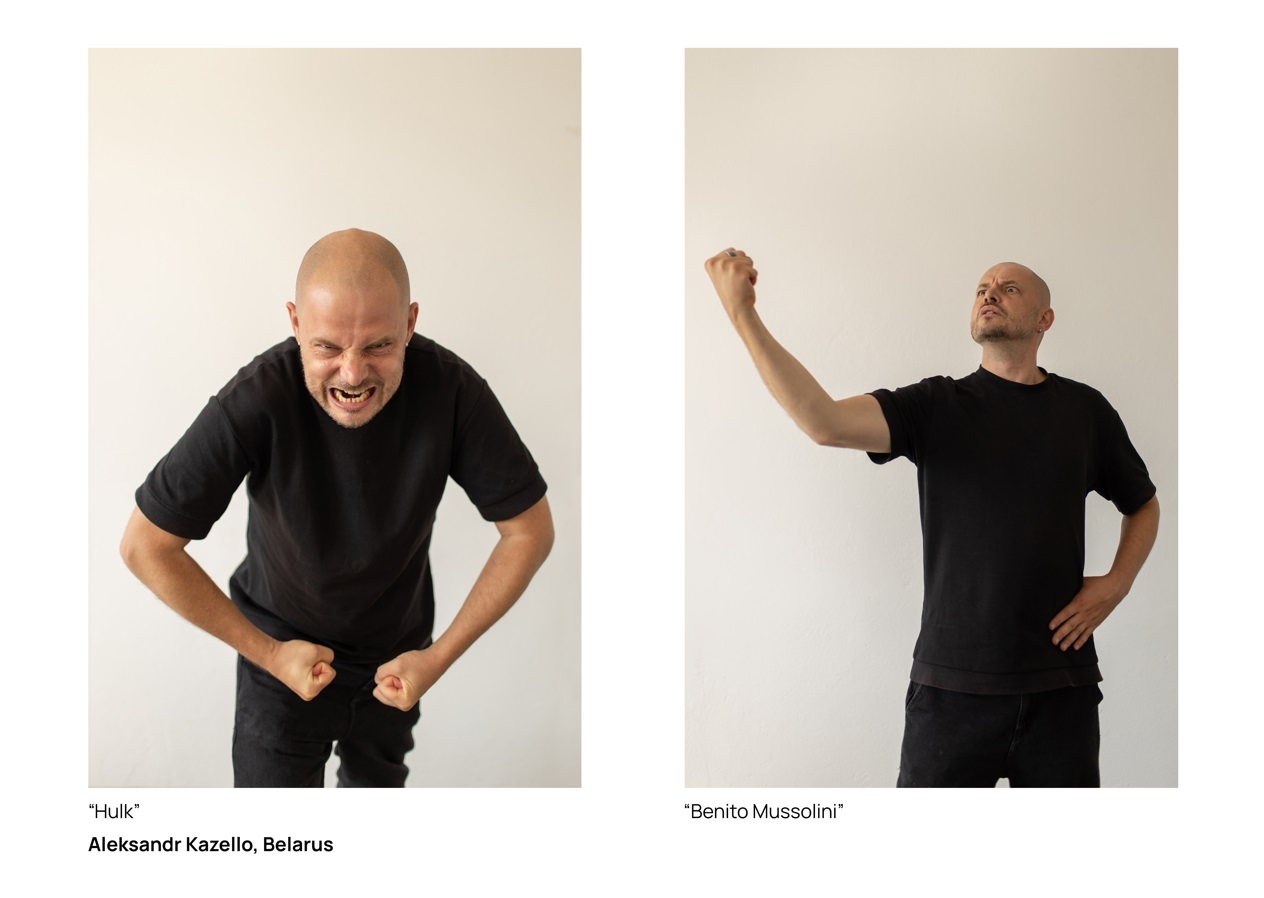

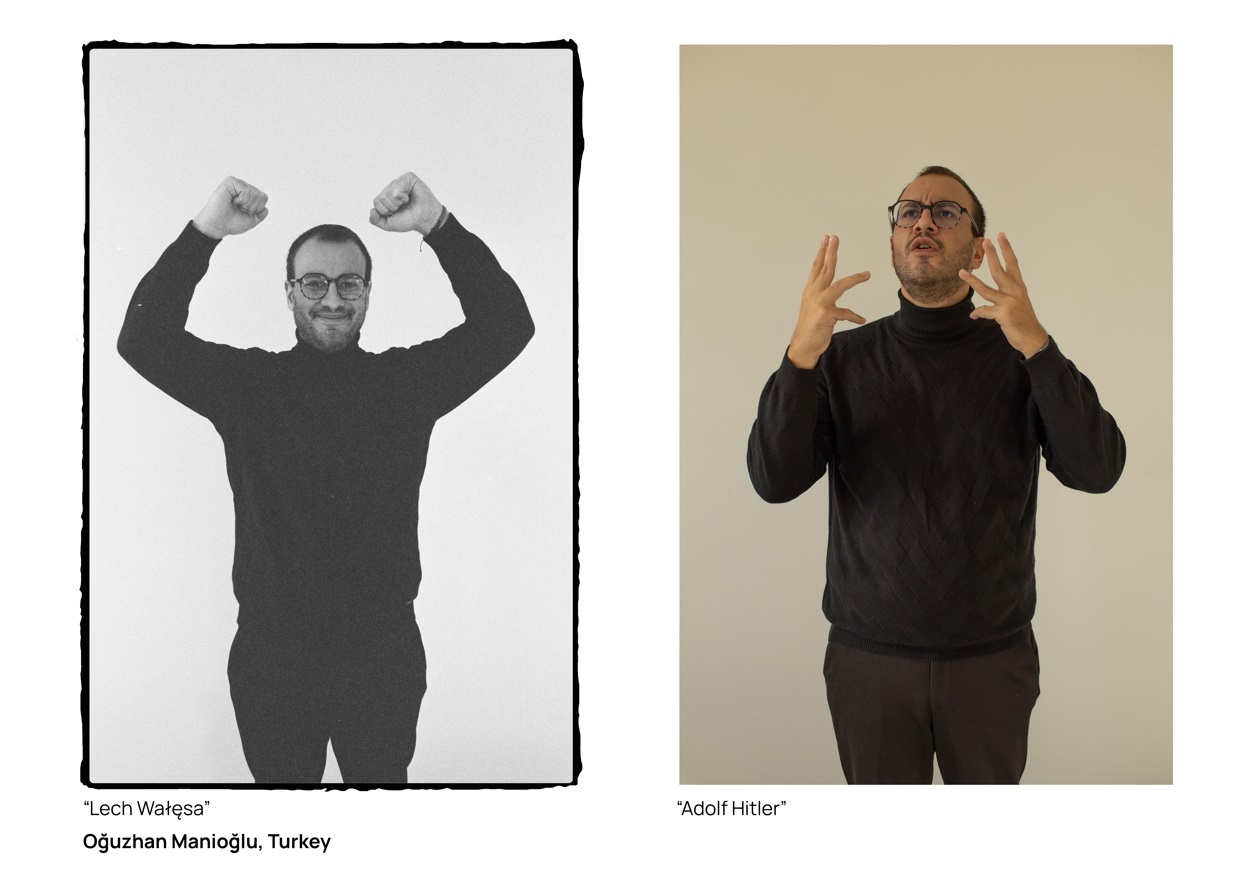

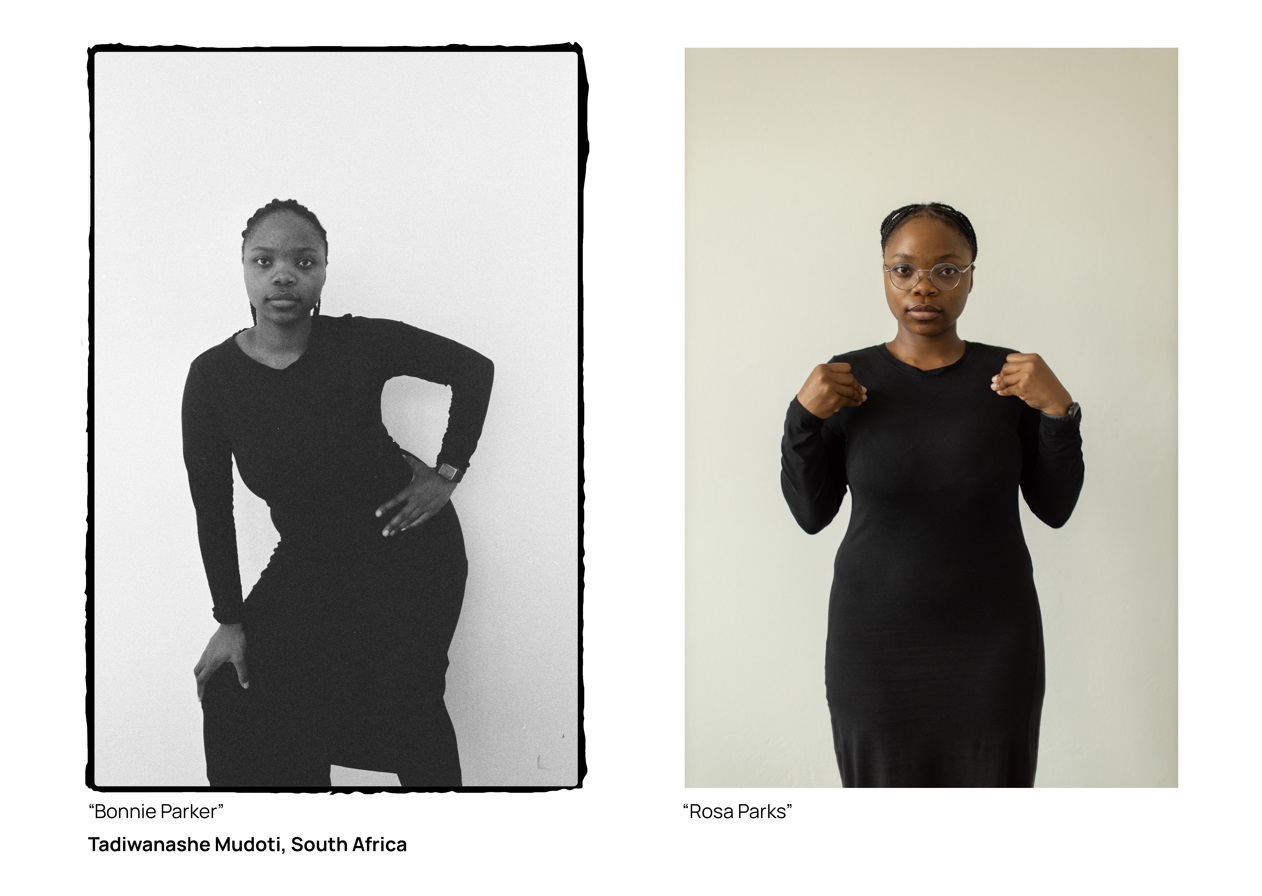

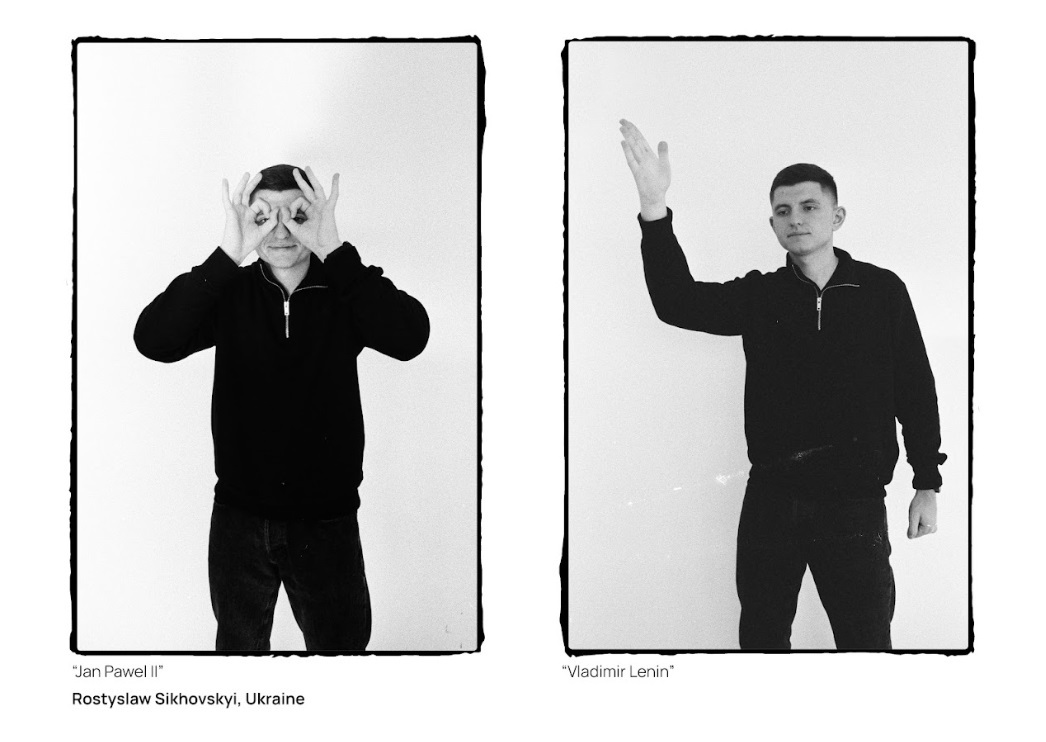

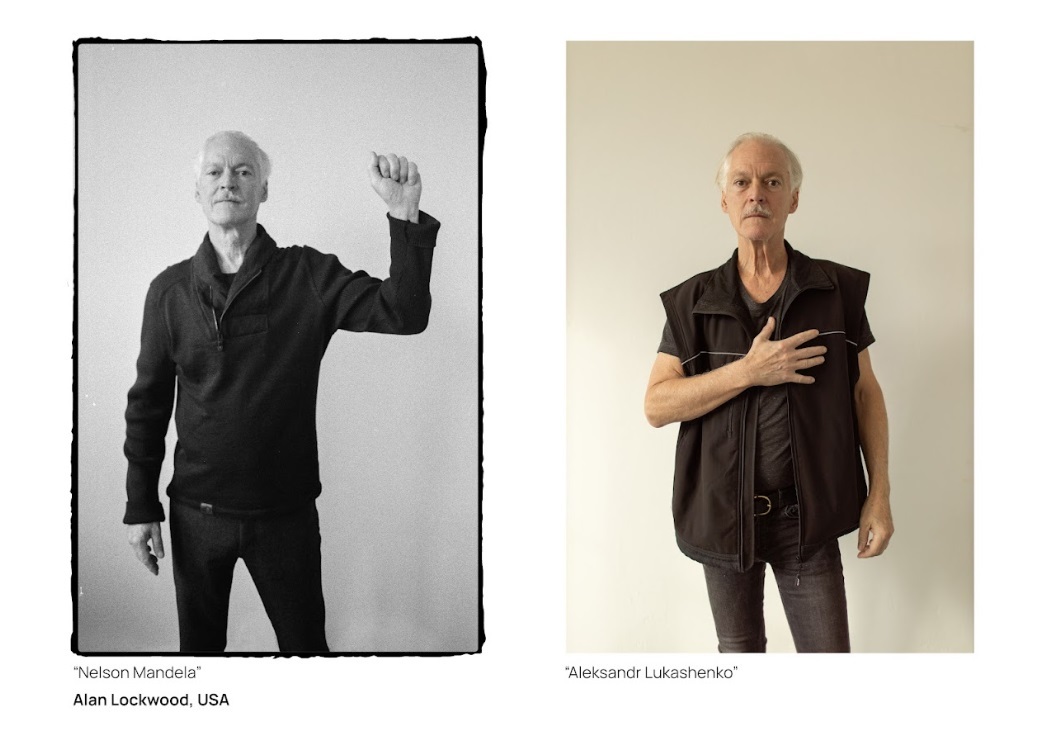

Before exploring the reproductive function of photography, it was important for me to find out how others understand this concept of »I-hero« and »I-antihero« in the modern world. So, I conducted a questionnaire survey in which more than 100 people were asked to name five heroes and five anti-heroes from the history of the last 100 years. I proposed my respondents to consider as »heroes« and »antiheroes« not only real personalities, but also imaginary characters, for example, from the world of cinema.

ZMICER WAYNOWSKI

The final list was already something interesting, but it was not what my end goal was. Following Gadamer’s concept, I then conducted an experiment to check how deeply rooted these images were in our perception and invited people of different cultural backgrounds to choose from my list one »hero« and one »anti-hero« and–using gestures, facial expressions and pantomimy only–to show them. Their pose was then something that I photographed. I did not interfere in the process or somehow tried to guide my respondents, but simply asked them to »portray« the images that exist in their minds.

Two hypostases of the same subject, in my opinion, should give the viewer an idea of the experiment participant, his or her identity and body language.

The resulting series of images helped me create one of the scenes of the play where I explore the role of the primary source, which allows the image to »appear.« There I also discuss moral and ethical aspects of the artist’s choice and personal responsibility, referring to the effect of the anti-hero’s »increase in being.«

Two parts of your play were written by the Belarusian art critic and photographer Olga Bubich. What underlay this creative tandem? Did you need another voice or a different perspective on the topic?

Offering Olga the opportunity to contribute with two parts to the text I had already written was a risk. While I had a structure and a synopsis in mind, I was unsure how to balance another author’s creative freedom within this framework. While it’s possible to offer praise for someone’s text while still requesting changes, there are limits to how much can be altered before the process becomes burdensome and confusing.

My strength lies in generating ideas and concepts, whereas working on a script often involves grappling with the urge to endlessly rewrite. However, collaborating with a co-author inevitably necessitates following the established structure. Even if doubts arise, they cannot be openly expressed, otherwise the entire project might collapse. Yet, when synergy is achieved, and you see your idea articulated in words that reveal previously unseen dimensions, there’s a special feeling akin to the silence in a theater that usually means a special connection between actor and audience.

I rarely write, but when I do, I prefer doing so while traveling, such as on a train. Writing in this transient state of motion provides a sense of ease and freedom of thought. Before embarking on my journey this time, I decided early on that I needed a »conversation« companion whose presence would help me avoid the inevitable self-portrait.

It was through co-authoring with Olga that the story truly became universal. My main character’s dialogue transcended time with a »thousand-facedness« easily recognizable by audiences, irrespective of their cultural or social context. Moreover, the narrative evolved into a story where the protagonist is liberated from gender stereotypes

You have already shown the play in several Polish cities. How did your public react to it? What do you think different people, with and without the experience of living under dictatorship, will see in your project?

As I have said, in the play there is a performative scene that »provokes« an active reaction from the audience, which serves for me as a kind of indicator of the arisen reciprocity. The speed of the public’s reaction and the degree of their emotional involvement is surprisingly unpredictable every time. In fact, we approach this scene with an open ending, and the viewer actually completes my story in words for me unexpected. And I find these words the best review of the performance because they are unbiased and honest in their spontaneity.

As for the experience of living under a dictatorship, I can say that the play touches on universal moral and ethical issues; in my opinion, it is easy for an international viewer to transfer the local processes of life under a dictatorship to the global stage–especially now, against the backdrop of a passing era and a change in the state of things. Such a change opens up a possibility of something new and generates interest. I think it is also why the performance is equally understandable to everyone mutually involved.